Unskilled & Unaware

In 1995, McArthur Wheeler robbed two banks in Pittsburgh in broad daylight. No mask, no hat, no hoodie. Just a big grin for the security cameras. He was arrested the same night.

I didn’t know this backstory until recently. Like many, I’d heard of the Dunning-Kruger effect — in discussions on bad decision-making — but I had to Google it up each time. Then I came across Wheeler’s story, and suddenly, it clicked.

Wheeler believed he was invisible. He had smeared his face with lemon juice, convinced it worked like invisible ink. He even took a selfie to test the theory. When his face didn’t appear (likely due to poor lighting or a camera glitch), he took it as proof. Lemon juice was his invisibility cloak.

This wasn’t a prank. Wheeler really believed it would work.The story inspired psychologist David Dunning and his graduate student Justin Kruger to study how people assess their own competence. In 1999, they published their findings in a now famous paper: unskilled and unaware of it.

They discovered something both hilarious and haunting: the less people know about a subject, the more confident they tend to be. Because they don’t yet know what they don’t know.

Faux G(r)eek

The Dunning-Kruger effect doesn't just manifest in criminals with citrus-based invisibility theories. It appears anywhere decisions are made, including at the highest levels of government and economic policy. Which brings me to a live demo of confidence outpacing competence that we all witnessed recently.

A friend sent me the formula used to calculate tariffs. I couldn’t comprehend the (il)logic, but I noticed it triggered a lot of folks. It’s all …

Turns out, this was not a joke — it was the actual formula credited to Peter Navarro, a Harvard-trained economist and the brains behind the Mar-a-Lago Fair Trade Manifesto (there’s a dedicated Discord channel for more details). Navarro’s formula calculates country-specific tariffs, based on variables like exports, imports, and Greek letters that haven’t seen this much traction in a while.

So far, no other economist agrees with him. That hasn’t stopped him.

In fact, US tariffs were assigned even to countries with no real exports — including one so sparsely populated it’s best known for penguins and ice. But when confidence outweighs coherence, every iceberg is seen as a threat to national security.

Which brings me back to Dunning-Kruger — it doesn’t just live in text books or TED Talks. Sometimes it wears a suit, speaks in PowerPoint, and signs executive memos.Navarro wasn’t using Greek as camouflage — he genuinely believes in the math. This isn’t a lie. This is what happens when confidence cosplays as calculus.

Bye Bye Miss American Pie

Drove my Chevy to the levee, but the levee was filled with subsidized apples, confusing tariffs, and something that looked like patriotism but tasted like chalk.

At the heart of it all, Navarro was fighting for someone. Not steelworkers. Not soybean farmers. Red Delicious shoppers.

You know who they are. You work with them. You may even love one.

They are the silent majority. The stoic and the bruised, the Red Delicious loyalists. The ones who believe apples shouldn’t taste good — just look apple-ish. Waxy, glossy, tough-skinned.

For too long, they’ve been mocked by the Fuji elite; the Gala cartel; the Pink Lady syndicate. But now, finally, they have a champion. A man who believes life is a struggle, and so apples should be too.

Navarro’s war on free trade is less about economics and more about aesthetics. He saw the rise of tastier imports as a direct attack on traditional American blandness. And he fought back the only way he knew how — with Greek letters and fury.

Like the Red Delicious apple, his policies are oddly shaped, hard to digest, and strangely resistant to feedback — a perfect Dunning-Kruger case study. And just as people kept buying those apples out of habit or fear, Navarro kept tweaking his formula with unwavering confidence — even when everyone else stopped asking for it.

Bye Bye Miss American Pie…

this’ll be the day that free trade cried..

We’re All Idiots

Wheeler had lemon juice. Navarro had a formula. But if we’re honest, all of us have our own lemon juice moments — though usually not in front of the cops or the world’s media.

Sometimes it’s a diet or exercise tip we picked up minutes before the party. Sometimes it’s confidently explaining blockchain at dinner, hoping no one asks a follow-up. And yes, some of us have even defended Red Delicious. These aren’t rare lapses. They’re everyday examples of how the Dunning-Kruger effect lives not just in headlines, but in meetings, group chats, and arguments about movies or medicine.

The problem isn’t ignorance — it’s premature certainty. That thrill of figuring it out can make us avoid checking whether we’re still right. It feels like clarity. It feels like truth. And that’s what makes it so persuasive — to ourselves, and to others.

We don’t have to be foolish to fall for it. We just have to be human.

When the Levee Breaks

Sometimes we recognize the mistake. We pause, reflect, maybe cringe a little. We re-read the article we shared too quickly. We listen instead of argue. That’s how learning happens — awkwardly, quietly, without applause.

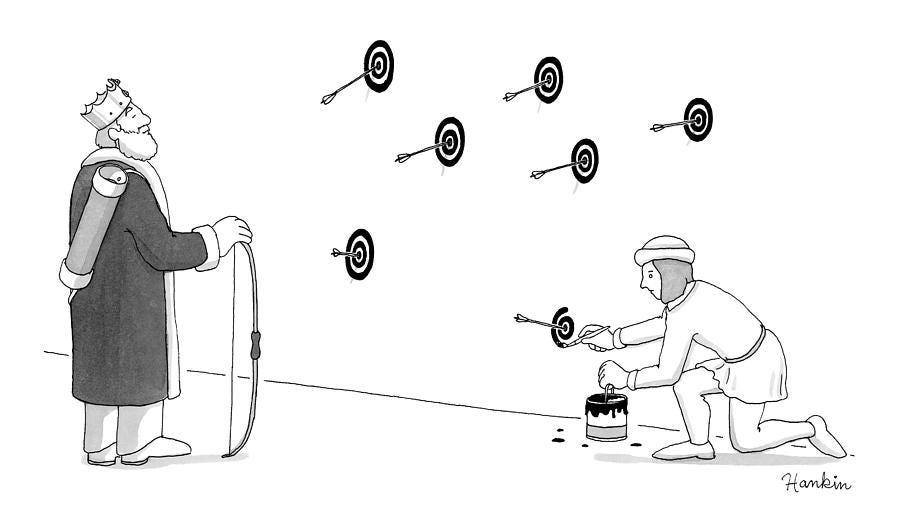

But often, we do the opposite. We dig in. We reinterpret the facts. We reframe the failure. We redraw the bullseye around wherever the arrow happens to land and declare victory.

Everyone makes mistakes. That’s unavoidable. But how we handle them — how we metabolize being wrong — is what distinguishes reflection from delusion. It’s where the sequel to every Dunning-Kruger moment begins.Some people go to jail. Some write bestsellers. Some get promoted. Most of us just do our best to avoid handing out lemon juice again with a straight face.

If you worry, don’t pray. If you pray, don’t worry.

Padre Pio

This is the kind of paradox that works for humility too. When you admit to the possibility that you might be wrong, you’re already closer to being right.

Maybe that’s what recovery from false confidence looks like. Not a grand confession. Just the quiet willingness to miss the mark without pretending the mark moved.

Enjoyed reading this.